Saturation divers are professional deep-sea divers who descend to depths of 152 metres or more to service equipment on offshore oil rigs and underwater pipelines. The depths to which they descend can reach up to 500 feet. However, in contrast to the majority of commercial divers, who spend only a few hours working underwater before returning to the surface, saturation divers will spend up to 28 days working on a single task. During this time, they will eat and sleep in a confined space that is pressurised to a high level.

The work that saturation divers do is demanding and can pay well (between $30,000 and $45,000 per month), but the setting under which they do it can be claustrophobic and unearthly. And doing so is not without risk. The Byford Dolphin was a Norwegian-operated oil rig that had an unfortunate accident in 1983 that claimed the lives of five people, including four saturation divers and one member of the crew.

The tragic sinking of the Byford Dolphin served as a wake-up call for the commercial diving industry, which promptly responded by instituting more stringent safety standards in order to make certain that no one else would suffer the same fate. First, before we go on to explain what took place, here is some information on decompression sickness, also known as "the bends."

Why 'The Bends' Should Not Be Taken Lightly

Divers have gained a lot of knowledge about how to safely swim to enormous depths since the invention of scuba diving in the 1940s, sometimes the hard way, and sometimes via trial and error. Every cell in a diver's body is subjected to pressure as they descend because of the weight of the water that is surrounding them. Even the molecules of gaseous nitrogen that are breathed in by the lungs become compressed when subjected to the pressure, which results in the gaseous nitrogen dissolving into the bloodstream.

The problem is not with the absorption of nitrogen in and of itself. When a diver attempts to return to the surface too rapidly after being submerged, they run into trouble. Imagine you're trying to remove the cap on a 2-liter bottle of soda after shaking it up. The bubbles formed instantaneously, and the expansion of the gases that had been contained under pressure.

This is essentially what takes place within the body of a diver who is experiencing decompression sickness, sometimes known as "the bends." The nitrogen molecules that had previously dissolved under pressure quickly expand and become gaseous again if the ascent from the high pressure of the deep water to the considerably lower pressure at the surface occurs too quickly.

"Nitrogen bubbles will form in the bloodstream, and those can prevent the circulation of blood, including to the heart," explains Phillip Newsum, an experienced commercial diver who is also the executive director of the Association of Diving Contractors International. Newsum is a member of the Association of Diving Contractors International. When this happens, you run the danger of developing a condition known as decompression sickness.

"The bends," also known as decompression sickness, is a painful condition that has the potential to be fatal. It can cause excruciating pain in the joints and muscles, as well as delirium, paralysis, heart attacks, and strokes. The condition known as the bends can be treated successfully if it is detected in a timely manner by placing the affected individual in a hyperbaric chamber, which is a specialised tank, and then gradually lowering the pressure in the chamber over the course of several hours or days.

However, the safest and most effective method to prevent decompression sickness is to gently ascend to the surface and take many pauses while doing so. This will allow your body to "off gas" the nitrogen in its system in a natural manner. Certified SCUBA divers are able to read a recreational dive planner, which informs them of when and for how long they should take safety breaks while ascending.

However, commercial divers are expected to work at depths that no recreational SCUBA diver would ever dare to attempt. These depths are significantly greater than those reached by recreational divers. As we will see in the following section, this calls for a completely different kind of decompression, and the fact that the system didn't work properly was the direct cause of the tragic deaths of the Byford Dolphin divers.

How Saturation Divers Are Able to Remain Submerged for Such a Long Time

When you go deeper into the water and stay there for longer periods of time, a greater amount of nitrogen will be dissolved in your bloodstream. The term "saturation diver" stems from the fact that a diver's body would eventually become "saturated" with dissolved nitrogen at some point during their dive.

Saturation divers are capable of working at depths of up to 304 metres (1,000 ft). It would take them days to reach the surface if they followed the same method as recreational divers to safely decompress after their dive, which is to slowly rise with extensive breaks in between each step.

Saturation divers, on the other hand, are brought to the surface in pressurised diving bells and then moved into specialised decompression chambers once they have reached the surface. A saturation diver must spend around one day in the chamber for every 100 feet (30 metres) that they descend. While they are there, they can relax on beds, watch films and get meals through pressurised slots.

The issue is that it is not cost-effective for an oil corporation to pay saturation divers for only a few hours of work in exchange for many days off between shifts. It's also fascinating to note that once you hit the saturation threshold, your body is unable to absorb any more nitrogen, regardless of how long you remain submerged for. Saturation divers do not undergo decompression after each dive; rather, they remain at the same pressure during the whole session.

The Byford Dolphin Accident: How 5 Deep-Sea Divers Met Grisly Deaths https://t.co/PlL8HbmiMZ via @HowStuffWorks

— Robert Bois le Duc (@Du1Boisle) June 24, 2023

Saturation divers will ride down to the depths in those pressurised diving bells for up to 28 days at a time, which is the maximum allowed by the industry. However, instead of going to the surface and entering a decompression chamber, they stay in a hyperbaric chamber, which keeps their body at the same pressure level as the deep water.

"We call that the storage depth," says Newsum, whose organisation helps to set worldwide safety standards for commercial diving. Newsum is a member of an organisation that helps to establish international safety standards. Because they are able to maintain their compressed state, they may continue working out there for as long as they need to, and you won't have to worry about decompressing them when you bring them back up to the surface.

That is, in order to complete the task at hand. Before eventually emerging from the confined space and inhaling fresh air for the first time in weeks, the final week of each saturation diving work is dedicated to the process of slow and steady decompression.

A Normal Process That Ends Up Going Terribly Wrong

For a saturation diving operation to be successful, it requires the participation of the entire crew.

It is the responsibility of the life support professionals to guarantee that the air mix in the hyperbaric chamber is identical to the air that the divers breathe when they are submerged. It is the responsibility of the dive control team to operate the diving bell, which is suspended from a crane, and to monitor the divers' progress while they are at work. Even though they are confined in the living chambers, the guys are attended to by cooks who bring them food and give it to them.

Related link : What Exactly Is CNC Machining, Anyway?

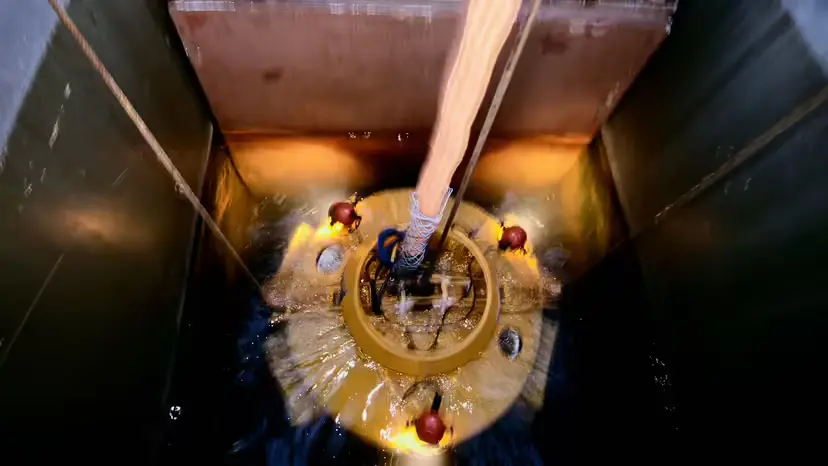

The support workers known as "tenders" are responsible for very vital tasks. They contribute to the process of unspooling and retracting the "umbilical," which refers to the bulky line of air supply tubes and communication wires that connects the divers to the surface. In the past, tenders were tasked with a variety of additional roles, one of which was to dock the diving bell to the pressurised dwelling chambers.

"The saturation divers are completely at the mercy of the tender and of their supervisors on the dive control team," adds Newsum. "They have no control over the situation at all."

On the 5th of November in 1983, an experienced tender by the name of William Crammond was in the middle of a normal procedure onboard the Byford Dolphin, a semi-submersible oil rig that was operating in the North Sea. The rig featured two separate pressurised dwelling chambers, each of which could accommodate two scuba divers. Crammond had just finished connecting the diving bell to the living chambers and safely delivering two divers to the first chamber. Chamber two was already being used as a resting spot for the other two divers.

That was the moment when everything started going terribly wrong. Under typical conditions, the diving bell wouldn't be removed from the living chambers until after the doors to those chambers had been successfully locked and the area was deemed safe. On the other hand, the diving bell came loose before the chamber doors were shut, resulting in what is described as a "explosive decompression."

According to Newsum, "It is a sentence of death." "There is no hope for you."

The air pressure inside the living chambers of the Byford Dolphin suddenly dropped from 9 atmospheres, which was the pressure that was felt when hundreds of feet below the ocean, to 1 atmospheric, which is the normal air pressure at the surface. Crammond was killed and his fellow tender, Martin Saunders, was badly injured when the heavy diving bell was launched into the air by the tremendous flow of air that was released from the chamber.

The situation was far worse for the four saturation divers who were inside. Three of the individuals who were inside the chamber, namely Edwin Arthur Coward, Roy P. Lucas, and Bjrn Giaever Bergersen, were effectively "boiled" from the inside when the nitrogen in their blood suddenly exploded into gas bubbles, as stated in the postmortem reports. They passed away in an instant.

The most horrific injuries were sustained by the fourth scuba diver, Truls Hellevik. When the pressure in the room was finally released, Hellevik was there to witness it. He was standing in front of the living chamber's door, which was only cracked open a crack. His body was sucked out through an aperture that was so small that it ripped him open and flung his organs out onto the deck as it passed through.

Difficult Lessons Taken, and Prolonged Delays in Bringing Justice to the Families

The discovery of oil in the North Sea off the coast of Norway in the 1960s marked the beginning of a period of significant economic growth in that region. There were times when safety was not the main priority. There were at least 58 people who drowned while diving in the North Sea between the years 1960 and the early 2000s, according to one tally.

"The Byford Dolphin was one of the worst oil field disasters in history," adds Newsum. "And it led to sweeping changes in the North Sea and in commercial diving safety worldwide."

According to Newsum, as of recently, it is mandatory for every diving activity to conduct a comprehensive risk assessment and hazard analysis. Every process has built-in safeguards called redundancies, which are designed to protect against mistakes either by humans or by malfunctioning machinery. Some oil rigs even have specially designed hyperbaric lifeboats that are capable of transporting saturation divers away from a hurricane or fire without having to first bring them back to the surface pressure.

Regrettably, it took several years for the Norwegian government, which had been in charge of operating the Byford Dolphin in the year 1983, to acknowledge its role in the tragedy and make amends to the families of the five men who were killed in the disaster. The Norwegian government did not hand up any of the hidden quantities of money to the families of any of the six victims of the accident that occurred in 1983, including Saunders, who was injured in the incident, until 2009. According to the investigation, the catastrophe was caused by faulty equipment and not by the negligence of any individuals. The Byford Dolphin rig was pulled out of service in the year 2016.